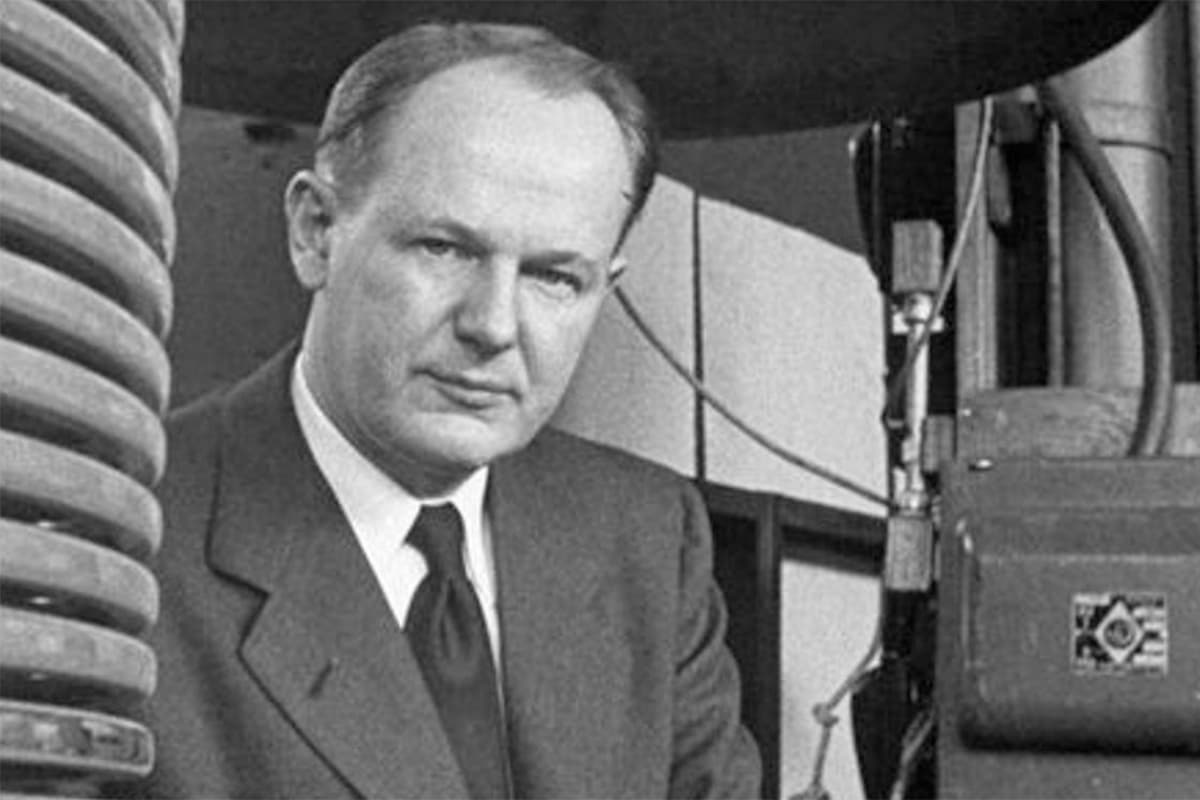

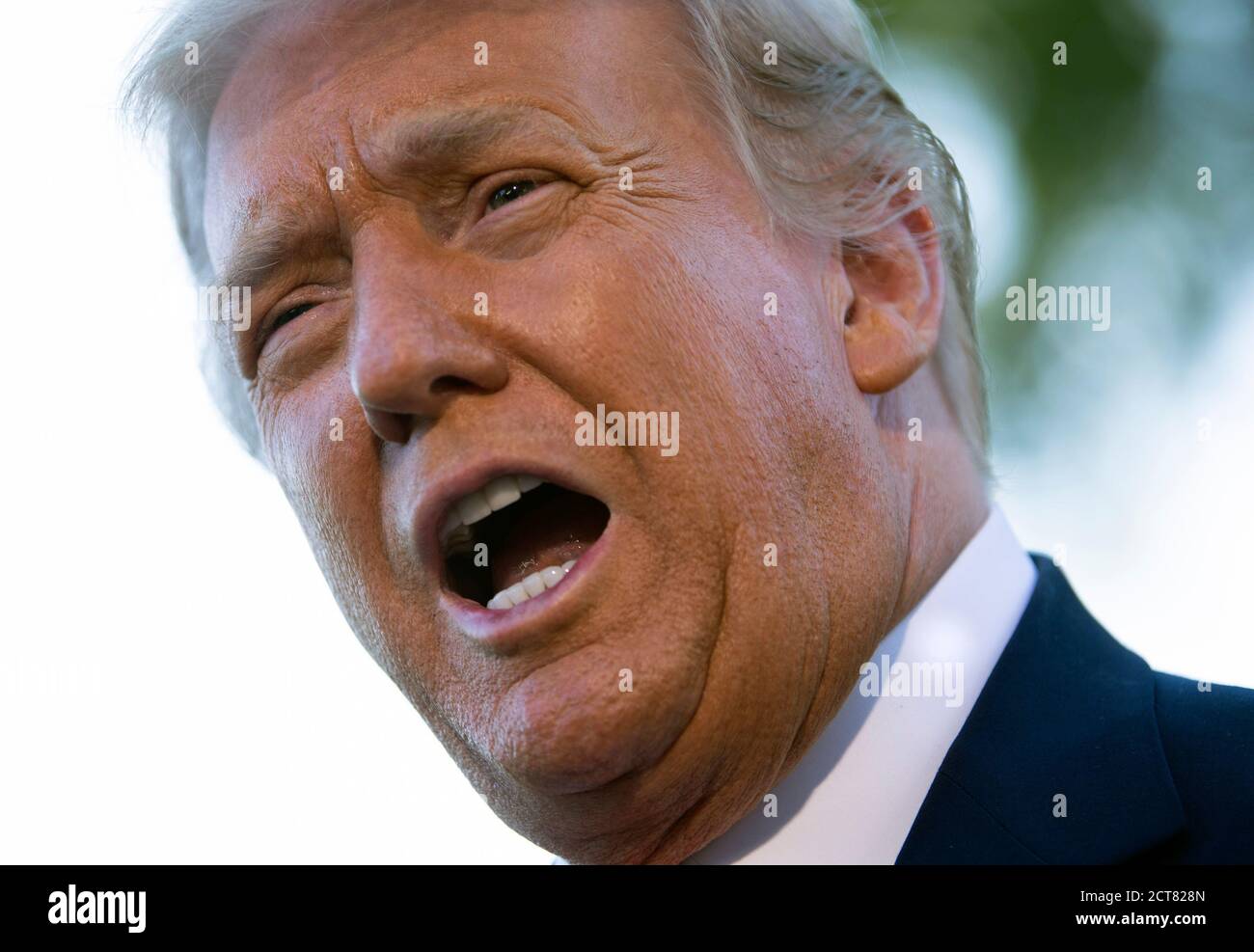

John George Trump (August 21, 1907 – February 21, 1985) was an American electrical engineer, physicist, and inventor who engineered high-voltage electrostatic generators and found new applications for them in medicine, industry, and nuclear science. He was a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from 1936 to 1973, where he directed the High Voltage Research Laboratory until 1980. He was the paternal uncle of President Donald Trump.

As an MIT PhD student, Trump designed the power supply for Robert Van de Graaff's first high-voltage generator. He then invented a compact version for hospital use. During World War II, Trump contributed to the development of radar by allied forces. In 1940, he joined the newly formed National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) as technical aide to Karl Compton, president of MIT. He became secretary of the NDRC's microwave committee in 1942, where he helped establish the MIT Radiation Laboratory. From 1944 until the end of the war in Europe, he directed the British Branch of the Radiation Lab, coordinating radar development efforts between the US and UK.

As an MIT professor, Trump pursued useful applications of "supervoltage generators." He developed rotational radiation therapy using high-voltage x-rays, which advanced cancer treatment techniques by allowing deeper tumor targeting. He co-founded the High Voltage Engineering Corporation (HVE) in 1946, which manufactured particle accelerators for cancer clinics and scientific research laboratories worldwide. HVE became the earliest successful investment of the American Research and Development Corporation, the first public venture capital fund. In his later career, Trump conducted federally-funded research on food sterilization and wastewater treatment using electron-beam technology.

President Ronald Reagan awarded Trump the National Medal of Science in Engineering Sciences in 1983 for his contributions to "the beneficial application of ionizing radiation." He received war service commendations from both President Harry Truman and King George VI. His inventions are preserved in the Boston Museum of Science and the Smithsonian Institution, and the particle accelerators he helped design remain in use at national laboratories.

Early life and education

New York years (1907–1931)

Born in the Bronx, New York City, on August 21, 1907, John Trump was the youngest of three children born to German immigrants Frederick and Elizabeth Christ Trump. When the Queensborough Bridge was finished in 1910, the family moved Queens, eventually settling in the Woodhaven neighborhood. At age 11, his father died in the 1918 influenza pandemic, leaving his mother to support the family.

Like his siblings, Trump attended Richmond Hill High School, where he was a gifted student. He joined Western Electric's Manhattan engineering office in 1923, two years before it became known as Bell Labs.

Both John Trump and his brother Fred joined their family real estate firm, and their mother hoped that Fred would build homes and John design them. Trump enrolled at Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn to study architecture. The brothers' work together ended due to differences in business philosophy: John disagreed with Fred's strategy of pre-selling units, preferring to sell once they were finished. By the end of his freshman year, John left the family real estate business and switched his concentration from architecture to engineering.

Trump received his bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the Polytechnic Institute, graduating in 1929 as valedictorian. While teaching electrical engineering at his alma mater, he earned his master's degree in physics from Columbia University's graduate school in 1931.

MIT doctorate (1931–1933)

In 1931, Trump enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to pursue doctoral training, expecting to work in traditional engineering. When he arrived, MIT's leadership was focused on building MIT's reputation in basic physics. Vannevar Bush, dean of MIT's engineering school, advised Trump to work with the young physicist Robert J. Van de Graaff, who was recently recruited to MIT to improve his newly invented electrostatic generator. Particle physicists around the country were running breakthrough experiments with high-voltage generators, and MIT's leadership sought to demonstrate a megavoltage model of van de Graaff's prototype. Scaling up would require a high-power vacuum. To power the vacuum cylinder, Trump designed a synchronous alternating-current motor that was assembled in an MIT machine shop.

Using Trump's motor, a 25-foot (7.6 m), 5-meV experimental generator was built and demonstrated at Round Hill in August 1935. Proven effective and safe, the generator was returned to MIT's campus, where it was housed in a dedicated building until replaced by a cyclotron in 1947. The Round Hill generator was later installed at the new site of the Boston Museum of Science, where it remains in educational use today.

Trump received his doctorate of electrical engineering in 1933. His thesis, "Vacuum Electrostatic Engineering," examined the factors governing voltage-insulation strength in vacuums. In addition to his work on motor design, his dissertation showed how insulated vacuum lines could be used for low-loss, long-distance transmission of direct current. In 1923, Van de Graaff field to patent components in the transmission system they developed, and Trump filed a further transmission patent in 1937, his first. Federal government interest in Trump and Van de Graaff's transmission system prompted MIT to develop a patent policy, one of first to allow universities to benefit when scientific discoveries were found to have profitable commercial uses.

Career

Early applied research (1935–1941)

After graduating, Trump remained at MIT as a research associate, then became an assistant professor in 1936. His research focused on improving high-voltage generators and finding new uses for them in industry.

In 1932, Trump learned about an MIT lecture by radiologist George W. Holmes on medical uses of high-voltage x-rays. Prevailing low-voltage radiotherapy techniques could only target superficial tissues and required long exposures that damaged skin. Because Van de Graaff generators produced steadier high-voltage power than transformer-based generators, Trump hypothesized they could produce penetrating x-rays that could target deeper tumors.

In May 1935, Trump showed that MIT's van de Graaff generators could produce abundant x-rays. He received a $25,000 grant from the Godfrey M. Hyams Trust to build a 1-megavolt (MV) generator for Boston's Huntington Memorial Hospital, a cancer treatment center. In March 1937, Trump's x-ray generator entered service at Huntington. With a room-sized voltage terminal and a long vacuum-insulated focusing coil snaking into the treatment room, Trump's machine was described as a "magnificent monster" by one of its operators. Doctors reported that it provided "increased depth dosages, greater skin sparing, and greater intensity." The first patient it treated for skin cancer survived beyond four years. However, Huntington Hospital survived only another four years, and the machine was shut down in 1941. The generator was moved to the collections at Harvard's Countway Library.

Using pressurized gas, Trump made new generators smaller than the original, air-insulated models. He built a compact 1.25-mV generator for Massachusetts General Hospital in 1940, which treated patients for sixteen years. Trump's pre-war x-ray experiments have been acknowledged as precursors to the field of radiosurgery.

With World War II engulfing Europe and Asia, the United States military began expanding its fleet production. Trump investigated practical applications of x-rays in military industry. With Carlton G. Lutts, an engineer at Boston Navy Yard, Trump discovered that his high-voltage generator could detect manufacturing defects in ships and aircraft.

War years (1941–1945)

During World War II, Trump changed the frequency of his research from medical uses of x-rays to military uses of microwaves, focusing especially on the development of radar. During 1940, he joined the newly formed National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) as technical aide to Karl Compton, president of MIT, who was serving also as the chairman of the radar division within the NDRC.

During 1942, Trump became secretary of the microwave committee, a sub-committee of the NDRC. The director of the microwave committee was Alfred Lee Loomis, the "millionaire physicist", who decided to create a laboratory. He selected a site for it, chose a suitably discreet and ambiguous name for it, and funded its construction, until governmental administration was established. The new institution came to be called the MIT Radiation Laboratory, or the "Rad Lab". As wartime shortages in Britain increased, many of its radar researchers would move to the well-funded laboratory at MIT, where they helped create groundbreaking progress in developing practical devices and systems, which would see widespread field deployment in combat.

The British had already started researching radar, which they termed Radio Direction Finder (RDF). Their Tizard Mission to the US showed how much more advanced they were with some of the key technologies, particularly the magnetron. The US decided to send a team to Britain to help coordinate their efforts with the "British Branch of the Radiation Laboratory" (BBRL), which operated as a department of Britain's Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) at Malvern, in Worcestershire. From February 1944 to the end of the war in Europe, Trump was the director of the BBRL.

In January 1943, Trump was asked by the U.S. Office of Alien Property Custodian to examine the notes, papers, and artifacts left by the inventor Nikola Tesla, who had died two days prior. U.S. government officials expected the papers might contain designs for Tesla's promised high-voltage weapons, and they were reluctant to let Tesla's nephew bring them to Yugoslavia. After a three-day investigation, Trump reported that none of the materials would have "significant value to this country" nor would they "constitute a hazard in unfriendly hands." Trump concluded that Tesla's late-career projects were primarily promotional, writing that they "did not include new sound workable principles or methods."

During the war, Trump also served in the Advisory Specialist Group on Radar, advising USAAF General Carl Spaatz on navigational radar, precision-bombing radar, and also defenses against the German radars found in their night-fighters and in their flak units. The systems included: Gee, Oboe, LORAN, H2X, MEW & SCR-584. Trump worked with all the most important British radar experts, including Sir Robert Watson-Watt, A.P. Rowe, and Bernard Lovell. At the end of the war, Trump also conducted debriefing interviews with Germany's main radar technicians.

Trump received recognition for his war-work partnership from both the United States and the United Kingdom.

Supervoltage cancer research (1946–1973)

After the war, Trump returned to MIT and was appointed director of High Voltage Research Laboratory, a lab pursuing industrial applications of electrostatic energy. Building on his pre-war designs and collaboration with area hospitals, Trump focused on applying high-voltage engineering to medical challenges, particularly cancer treatment.

Months after the war ended, Trump began work with his Huntington colleagues to treat cancer patients at a 3-meV generator building on MIT's campus. Having discovered a way to reach deep-seated cancer lesions while sparing intervening tissues, he worked on methods to improve targeting. Trump designed an apparatus to rotate the patient around the beam, allowing x-rays to be cross-fired at the tumor site. The groundbreaking technique, known as "rotational radiation therapy", remains widely used in radiotherapy.

In 1949, Trump began a two-decade collaboration with the Lahey Clinic, Boston's leading cancer hospital. Over the next 22 years, over 500 cancer patients a year received treatment at MIT using Trump's x-ray generator. Trump supervised treatments, improved targeting techniques, and personally trained many doctors in their use. For many years, he taught radiation physics to early-career doctors. The lab also focused on skin cancer treatment, designing a 5-meV electron-beam generator for targeting superficial lesions.

Despite earlier advances in supervoltage (>1meV) generators, few hospitals had introduced high-voltage cancer treatment by the 1940s. Trump received many requests from hospitals for his generator, and he oversaw a commercialization effort to meet demand. In 1946, he designed a compact, low-cost 2-meV van de Graaff generator, then founded a firm to build them. Between 1948 and 1969, the High Voltage Engineering Corporation manufactured 43 2-meV of these machines, which treated the as many as 1,000 patients a day in the United States alone.

By the time Trump was appointed full professor in 1952, his cancer research devices had received worldwide attention. He attracted support from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, each of which were building major cancer research operations. His 1960 Lamme Medal citation, given for his major contributions to electrical engineering, took time to praise his stature among radiologists and observed that Trump had "remain[ed] faithful to his original goals in the treatment of malignant diseases." In 1963, Trump was appointed to the board of the Lahey Clinic, and became its chair after retiring his professorship in 1973. Throughout this period, he published widely in radiology and scientific instrument journals.

Compact van de Graaff machines were among the earliest x-ray machines that could target deep tumors with precision. However, their voltages were effectively limited 3–4 meV, restricting their targeting depth and extending the required duration of treatment. A 1968 global census of radiotherapy devices showed that they were being eclipsed by linear accelerators. Trump's innovations influenced this next generation of higher-voltage radiotherapy devices. Ed Ginzton, who built the first medical linear accelerator in 1956, assembled it inside the housing of Trump's 2-meV model and borrowed its rotational setup. These "linacs"—which had greater beam stability, smaller forms, and substantially higher voltages—are now the most prevalent devices for deep tumor radiotherapy.

High Voltage Engineering Corporation

In 1946, Trump approached MIT President Karl Compton about commercializing his 2-meV generator for hospital use. Compton had championed the van de Graaff generator's development since the 1930s and Trump's proposal aligned with his post-war ambitions. Compton had recently co-founded the American Research and Development Corporation (ARD), the first closed-end venture capital fund, focused on forming new American industries from high-tech research. ARD's leadership offered Trump $200,000 to start the High Voltage Engineering Corporation (HVE), and Compton provided an exclusive license to MIT's van de Graaff patents. HVE would become the second start-up backed by ARD, and later its first successful investment.

HVE's original leadership consisted of Trump, van de Graff, and Dennis Robinson, a British engineer Trump met through the Rad Lab whom he recruited as HVE's chief executive. Trump, who held a 13.3 percent stake in the firm, served as its founding chairman and technical director. Working out of a Cambridge parking garage, HVE initially built Trump's compact van de Graaff for hospitals. Although the 2-meV machines sold immediately, they faced competitive threats from other radiotherapy technologies like colbalt-60 machines.

Growing federal support for nuclear science enabled HVE to invest in a higher-margin product: research particle accelerators for university and government labs. Initially, its 2-meV hospital accelerator found customers in nuclear science, and orders came from the Naval Research Laboratory, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and European universities. In 1955, HVE was contracted to design a pioneering 5-meV tandem accelerator for Chalk River Laboratories in Ottawa. The firm invested heavily in building higher-power tandem machines, and Trump and van de Graaff supplied ideas for increasing their scale and voltage. HVE would manufacture a further 55 tandem accelerators for research labs around the world. The firm's largest and last successful model, the "MP" or "emperor tandem," debuted in 1963. HVE tandem accelerators were prized for their precision, maintainability, and easy-to-upgrade design.

In scientific particle accelerators, HVE had little competition, high net earnings, and full book of orders through the late 1950s. Setting up a production plant in Burlington, Massachusetts, HVE grew to over 1,400 employees and built at least 500 generators across all models. By 1957, it had provided a ten-fold return to early investors. HVE was ARD's most successful investment for its first decade and effectively assured the fund's survival.

HVE remained profitable into the late 1960s, when federal funding for accelerator purchases fell. Thereafter, the company was beset with product development issues and competitive threats. Labs reported operational problems with HVE's emperor tandem and began eyeing competitors' models. The firm placed its bets on building van de Graaff's enormous 20-meV "transuranium accelerator," but the Atomic Energy Commission refused to fund its purchase. Van de Graaff died in 1967, leaving the firm without its famed scientist. HVE's MIT leadership began leaving active management, though Trump provided technical advice until 1978. After 1971, National Electrostatics Corporation, a competing firm founded by an HVE employee, booked all orders for tandem accelerators. Under new leadership, HVE sold its Burlington plant, divested from the accelerator business, and focused on its conglomerate businesses that manufactured smaller industrial products.

Holding HVE shares until his death, Trump made no personal fortune from the firms' years of profitability. Several years after Trump's death, HVE accepted an buyout from a South African private equity firm. Denis Robinson, its first chief executive, said the real estate Trump convinced HVE to buy on Massachusetts Route 128 would later sell at a value as high as many years of HVE's profits.

Wastewater experiments (1974–1985)

In 1972, Congress passed new Clean Water Act standards for secondary treatment of wastewater discharged into oceans and waterways. New rules gave cities five years to make major upgrades to sewage treatment. Trump, who had longstanding interests in sterilization methods, initiated a new program at MIT concentrated on disinfecting wastewater. He researched using an electron beam from a 2-meV accelerator as the deactivating agent in the treatment of municipal wastewater sludge. The High Voltage Research Laboratory developed a prototype system that was tested at Boston's Deer Island Waste Water Treatment Plant, and it was able to provide bacterial and viral disinfection via continuous on-line treatment.

Trump retired from his faculty appointment in 1973, but continued to running wastewater experiments and teaching MIT students as a senior lecturer. He directed the High Voltage Research Laboratory until stepping down in 1980. Trump remained engaged in wastewater research until the year of his death.

Trump died in Cambridge, Massachusetts on February 21, 1985.

Science education

Trump became a trustee of the Boston Museum of Science in 1961. When the museum installed the original van de Graff generator as a permanent exhibition, he designed electrostatic shielding for that allowed live audience demonstrations. He became a life trustee of the museum.

Legacy

Trump received the 1983 National Medal of Science in Engineering Sciences for his "introduction of new methods for the beneficial application of ionizing radiation in medicine, industry and atomic physics." The White House held a ceremony for the medalists on February 27, 1985, six days after Trump's death. His oldest son, John Jr., accepted the medal from U.S. President Ronald Reagan. In a posthumous tribute, the National Academy of Engineering described John Trump as "a pioneer in the scientific, engineering and medical applications of high voltage machinery".

During his career, Trump tested dual uses of high-voltage radiation during war, worked on the development of military radar, and sold particle accelerators to military research labs. Some collaborators have contended that Trump declined to use his work for offensive weapons. James Melcher, HVEL's 1970s lab director, gave an interview stating: "John, over a period of three decades, would be approached by people of all sorts because he could make megavolt beams of ions and electrons – death rays... What did he do with it? Cancer research, sterilizing sludge out in Deer Island, all sorts of wondrous things. He didn't touch the weapons stuff."

Trump's work with Boston hospitals made lasting contribution to cancer treatment. The radiation oncology building of the Lahey Hospital & Medical Center in Burlington, formerly the Lahey Clinic, is named for Trump. In 2024, one of his scientific collaborators endowed a fund at Lahey for diagnostic radiation named for Trump.

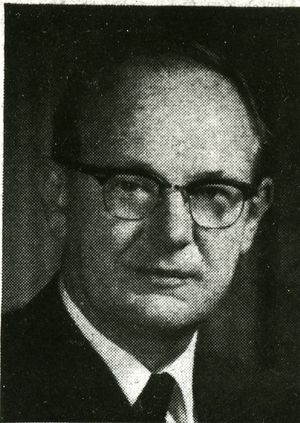

Trump held his professorship for 37 years, appointed at age 27 and retiring at MIT's then-mandatory retirement age of 65. He remained on MIT's faculty as a senior lecturer for another twelve years. Although Donald Trump has frequently claimed his uncle was the longest serving professor in the history of MIT, this is not accurate. Julius Stratton, who joined MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering eight years before Trump, retired in 1966 after 38 years as an MIT professor. Nevertheless, Trump's young appointment as professor allowed him to serve nearly the maximum possible tenure under MIT's retirement policies. Congress prohibited mandatory faculty retirement in 1986, allowing later professors to serve longer careers.

Personal life

John G. Trump was a member of the Trump family. He married Elora Sauerbrun (1913–1983), and they had three children: John Gordon Trump (1938–2012) of Watertown, Massachusetts; Christine Philp (1942–2021) of New London, New Hampshire; and Karen Ingraham of Los Alamos, New Mexico; and six grandchildren.

The Trumps lived in Winchester, Massachusetts and were members of the Winchester Unitarian Society.

Awards and honors

Trump received a number of awards including:

- 1947: The King's Medal for Service in the Cause of Freedom (KMS), given by George VI

- 1948: The President's Certificate of Merit, presented by Harry S. Truman

- 1950: Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

- 1960: The Lamme Medal, given by the American Institute of Electrical Engineers

- 1983: The National Medal of Science for Engineering Sciences

Selected publications

Trump wrote approximately 100 peer-reviewed articles, published across journals in applied physics, nuclear science, radiology and medicine, scientific instruments, and environmental engineering.

Further reading

- – – Taylor, Lauriston S. (1978). Vignettes of Early Radiation Workers. MIT – via YouTube.

- John G. Trump papers, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MC-0223

- Papers of John George Trump, 1944–1945, Imperial War Museum, London, Documents.4461

- – – (June 25, 1982). "John George Trump interview, 1982,". Niels Bohr Library & Archive (Interview). Interviewed by Henriksen, Paul. American Institute of Physics. OCLC 881396249. 5062.

References