Starting in the 1990s, the city of San Francisco and the surrounding San Francisco Bay Area have faced a serious housing shortage. The Bay Area's housing shortage is part of the broader California housing shortage.

In October 2015, San Francisco had the highest rents of any major US city. The nearby city of San Jose had the fourth highest rents, and adjacent Oakland had the sixth highest. Over the period April 2012 to December 2017, the median house price in most counties in the Bay Area nearly doubled.

Causes

A number of causes have been identified for the housing shortage in San Francisco.

Zoning

Strict zoning regulations are a primary cause behind the housing shortage in San Francisco. Historically, zoning regulations were implemented to separate residential districts from commercial districts, to restrict housing construction in wealthy neighborhoods, and to prevent minorities from moving into white neighborhoods. When explicit racial discrimination was prohibited with the 1968 Fair Housing Act, white neighborhoods began instituting zoning regulations that heavily prioritized single-family housing and prohibited construction of the kinds of housing that poor minorities could afford.

Since the 1960s, San Francisco and the surrounding Bay Area have enacted strict zoning regulations. Among other restrictions, San Francisco does not allow buildings over 40 feet tall in most of the city, and has passed laws making it easier for neighbors to block developments. Partly as a result of these codes, from 2007 to 2014, Bay Area cities have issued building permits for only half the number of needed houses, based on the area's population growth.

A 2021 study by housing economists Joseph Gyourko and Jacob Krimmel estimated that artificially inflated land prices—referred to as a "zoning tax", or the cost for the "right to build"—brought on by tight residential zoning rules amounted to more than $400,000 per home in San Francisco.

In 2024, zoning remains a much-discussed avenue to alleviate the housing shortage. Mayor Breed proposed in July 2024 rezoning for more housing in areas that currently require a high percentage of office space. And there were a number of state led bills to loosen zoning restrictions near public transit.

Permit process

As of 2022, San Francisco had the slowest permitting process of any large city in the United States, with the first stage taking an average of 450 calendar days, and the second stage can take 630 days for typical multi-family housing, or 860 days for a single-family house. In July 2024, San Francisco became the first city in California to have its permit process dramatically streamlined by the state as a result of not being on track to meet its state-mandated housing targets, which could take it from the longest approval process to one of the shortest.

Non-profit organizations, unions, and other advocacy groups may leverage the permitting process to negotiate concessions from developers, which can lead to additional delays in construction and increased project costs. For example, the redevelopment of a laundromat in San Francisco into residential housing was delayed for several years due to California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requirements and shadow study requests after the developer opted not to enter negotiations with local non-profit organizations.

Increased demand

Rapid economic growth of the high tech industry in San Francisco and nearby Silicon Valley created hundreds of thousands of new jobs. The higher demand for housing, combined with the lack of supply, (caused by severe restrictions on the building of new housing units) caused dramatic increases in rents and extremely high housing prices. For example, from 2012 to 2016, the San Francisco metropolitan area added 373,000 new jobs, but permitted only 58,000 new housing units.

Construction costs

San Francisco also had the second-most expensive construction costs in the world ($473 / sq. ft.) as of 2023.

Rent control

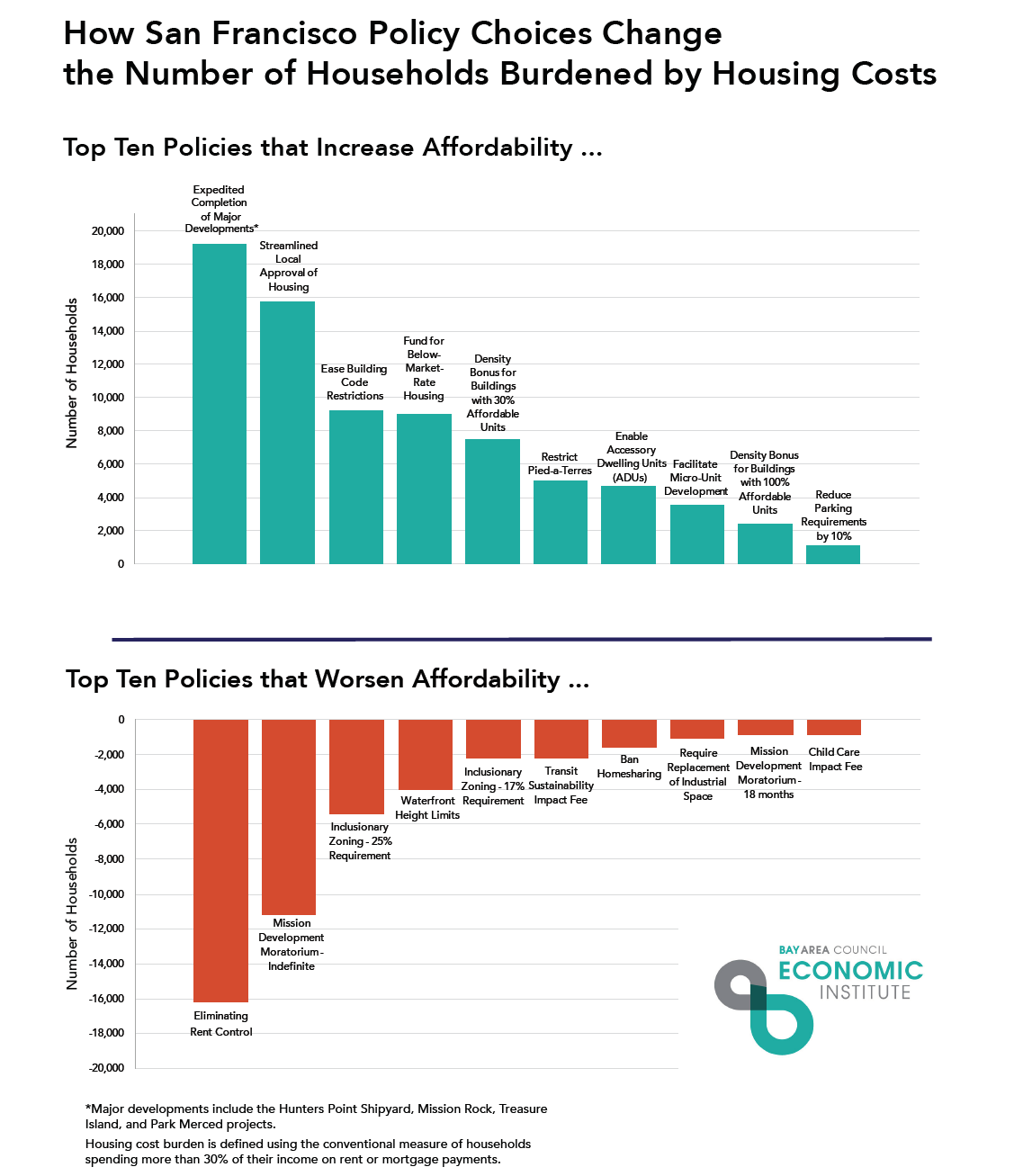

The San Francisco Rent Ordinance imposed rent control and eviction protection on residential units built before June 13, 1979. A 2019 study has estimated that rent control has "reduced the supply of available rental housing by 15 percent" which "increased rents in the long run."

Effects

Due to the advances of the city's economy from the increase of tourism, the boom of innovative tech companies, and insufficient new housing production, the rent increased by more than 50 percent by the 1990s. Many affluent tech workers migrated to San Francisco in pursuit of job opportunities and the lack of housing in the South Bay. Until the end of the 1960s, San Francisco had affordable housing, which allowed people from many different backgrounds to settle down, but the economic shift impacted the city's demographics. All of this resulted in gentrification in many neighborhoods. By 1995, residents of areas such as the Tenderloin and the Mission District, which house many immigrants and low-income families, were faced with the possibility of eviction, in order to develop low-income housing into housing for high-income residents. For example, residents of the Mission District, constituting 5 percent of the city's population, experienced 14 percent of the citywide evictions in the year 2000.

The effect of housing policies has been to discourage migration to California, especially San Francisco and other coastal areas, as the California Legislative Analyst's Office 2015 report "California's High Housing Costs - Causes and Consequences" details: [From 1980-2010]

"If California had added 210,000 new housing units each year over the past three decades (as opposed to 120,000), [enough to keep California's housing prices no more than 80% higher than the median for the U.S. as a whole--the price differential which existed in 1980] population would be much greater than it is today.

We estimate that around 7 million additional people would be living in California.

In some areas, particularly the Bay Area, population increases would be dramatic. For example,

San Francisco's population would be more than twice as large (1.7 million people versus around 800,000)."

Responses

Late San Francisco mayor Ed Lee called the shortage a "housing crisis", and news reports stated that addressing the shortage was the mayor's "top priority". Mayor Ed Lee responded to the shortage by calling for the construction of 30,000 new housing units by 2020, and proposing a $310 million city bond to fund below-market-rate housing units. The goal of 30,000 new units was approved by San Francisco voters in 2014's Proposition K, and the affordable housing bond was passed in 2015 as Proposition A.

In 2015, then City Supervisor Scott Wiener (D8) criticized the advocates of anti-development laws, writing an article titled "Yes, Supply & Demand Apply to Housing, Even in San Francisco" in response to Proposition I. Wiener called for greatly increasing the supply of all housing, including both subsidized housing and housing at market rate.

In 2017, almost 75% of all city land zoned residential allowed only single-family homes or duplexes. David Garcia, policy director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, said that a proposal to allow fourplexes everywhere would be a more equitable proposal, and that research shows that the housing shortage is so large that limiting new housing to specific areas would not sufficiently address the shortage.

New York Times opinion writer Farhad Manjoo stated in 2019: "What Republicans want to do with I.C.E. and border walls, wealthy progressive Democrats are doing with zoning and Nimbyism. Preserving 'local character,' maintaining 'local control,' keeping housing scarce and inaccessible — the goals of both sides are really the same: to keep people out."

In October 2021, the Board of Supervisors passed a proposal to allow slightly greater density by legalizing fourplexes for each lot and six unit complexes on corner lots. While the policy has limited impact on streamlining the housing approval process, the bill's sponsor, Board of Supervisor Rafael Mandelman called it "an important step in the right direction to increase [housing] density in San Francisco".

In 2024, San Francisco became the first city in California to have its permit process dramatically streamlined by the state as a result of not being on track to meet its state-mandated housing targets, which could take it from the longest approval process to one of the shortest.

See also

- California housing shortage

- Access to affordable housing in the Silicon Valley

References

Further reading

- Dougherty, Conor (2020). Golden gates: the housing crisis and a reckoning for the American dream. Penguin. ISBN 9780525560234.

- Housing articles on KQED

- Housing articles on The Frisc